Physical Energy in the Parlanti Yard

Physical Energy in the Parlanti Yard

From museum pieces to public monuments, from small gold medals, silver spoons and polychrome maquettes to huge statues, the Parlantis have cast them all. Their castings were produced by both the lost wax process (direct and indirect) and the sand process. Castings were in various bronze alloys, aluminium, lead, silver and plaster. However, it is for works cast in bronze by the cire perdue (or lost wax) process that the Parlantis are most renowned.

Around about the time that the Parlantis arrived in Great Britain in the 1890s, there were very few artisans skilled in art bronze casting. Even by 1901 the situation was not much better. Writing in British Sculpture And Sculptors Of Today Marion Spielmann highlighted the shortage of art bronze founders in the UK: The point is well appreciated in Paris, where a dozen years ago there were two firms of fine-art bronze-founders employing over five hundred hands, whose work was very highly paid; while there were innumerable smaller establishments , and more were to be found in other cities of France. Since that time the ”new art” movement has there given an impetus to the art-trade such as should startle Birmingham into unaccustomed envy. In England such an industry is practically unknown, and it may be doubted if in the whole kingdom a hundred hands are employed in this production of bronze statuary, as distinguished from the ordinary metal figures and ornaments of commerce. Obviously, there is here an opening for a very beautiful and a very lucrative industry if only the public will understand its charm, and encourage the effort now being made to bring before the world good work by our best sculptors and designers.

The purpose of this website, which has been compiled by Steve Parlanti, is to promote awareness of the importance of the Parlanti art bronze foundries, which were active in the UK between about 1890 and 1940. All too often, the skill of the art bronze founder is overlooked, but without them we would not be treated to the wonderful bronzes that are to be found worldwide.

Records for casting from this period, both from foundries and sculptors, are difficult to come by, and for this reason this website is far from a comprehensive database of the Parlanti’s casts. Research is ongoing, and the list of confirmed Parlanti casts is always being added to. The ‘Sculptors’ and ‘Castings’ pages are regularly updated. However, working from a hand written list of Parlanti casts sited in London alone, it is clear that in a large number of cases Parlanti casts were not marked. Given that the handful of other art bronze foundries of the time did, in the main, seem to mark their casts, it means that any unmarked bronze produced during the years that the Parlanti foundries were active may be one of the large number of bronzes that Parlanti produced but that have yet still to be discovered or confirmed.

The Parlantis are mentioned in a number of art publications but sometimes without going into detail, meaning we have a tantalising lead of what they might of cast without being certain. Sir Jacob Epstein, when writing about his Madonna And Child of 1927, said While the bronze was still at the foundry Lord Duveen asked me if he could see it, and we motored to the workshop in Fulham. Which art bronze foundry in Fulham we do not know. In Evelyn Silber’s The Sculpture of Epstein she writes The Risen Christ was cast by Parlanti who also cast many of the 1920s portraits. Christopher Neve’s book on Leon Underwood states Before Underwood had been to Spain and recognised the importance of doing his own casting, the piece (Flux) was cast, like many of the others, by Parlenti (sic). Even in Susan Beattie’s seminal work The New Sculpture she writes Gilbert (Alfred) favoured the Compagnie de Bronzes in Brussels and, during the late 1890s, the Italian founder Parlanti at Parson’s Green. Alfred Drury too used Parlanti while maintaining a steady working realationship with Singer & Sons.

A good example of the difficulty faced when trying to confirm the casting foundry concerns a bronze work called Youth by the sculptor Alexander James Leslie (1873-1930). Leslie exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy between 1901 and 1922, as well as exhibiting elsewhere. In 1920, Leslie exhibited Youth-bronze statue, as well as two marble works (Iphigenia and The Muse of Theocritus), at The Royal Scottish Academy exhibition. He gave his address as The Studio, Parlenti’s (sic) Foundry, Beaumont Rd, West Kensington, London W14. With Leslie giving that address, there is certainly a high likelihood that the bronze statue exhibited at the RSA in 1920 was cast by Parlanti at his Beaumont Road foundry. Leslie had previously exhibited Youth at a number of other exhibitions. The description given in each case doesn’t always clarify whether it was the same work, if it was a different cast, or, sometimes, what medium it was in. In 1907 at the Royal Academy exhibition in London Leslie exhibited two works, one of which was Youth-bust. A bust not a statuette, and the medium is not stated. His address at the time was given as 8 Weymouth Avenue, Ealing, W. which was some 6 or so miles from Parlanti’s foundry at Parsons Green, London. In 1913 we find Leslie exhibiting Youth-statuette bronze at the Royal Academy in London, and in 1919, again at the Royal Academy in London, we find Youth-statue, bronze, both years giving his address again as 8 Weymouth Avenue, Ealing, W. Interestingly, when exhibiting 3 works at the Royal Academy in 1920 he gives his address not as Parlanti’s foundry, as he had done for the 1920 Royal Scottish Academy exhibition, but as 6 Gloucester Road, Ealing, W.5. Leslie also used his Youth for the Hawick WWI memorial in 1921. This was cast by McDonald & Creswick of Edinburgh.

Hawick WWI Memorial by Alexander J Leslie, using ‘Youth’ bronze

Photo credit: Mike Allport / Art UK

This illustrates how in the absence of a foundry mark or a paperwork trail, just how difficult it is to prove the casting foundry. All of the castings listed on the ‘Castings’ section on this website are either castings by Parlanti that have been confirmed by various means (which the writer is happy to provide details for, please use the contact page) or, where shown, are listed as ‘attributed’ to when the evidence is very high already but either further research is needed, or where there is no possibility of ever knowing for certain.

The ‘Sculptors’ page now includes a list of people of note who had dealings with the Parlanti foundries, compiled from a list written by Ercole Parlanti. The writer of the website has far more information than that contained within this website and would be happy to receive any enquiries or comments through the ‘Contact’ page.

Of particular importance is the distinction between Alessandro Parlanti, and his younger brother by some nine years Ercole Parlanti. Company headed papers show the foundry known as Alessandro Parlanti was in operation at 59 Parsons Green Lane, Fulham from 1895 to around 1917, and that Ercole ran his foundry at Beaumont Road from about 1917 onwards having worked alongside Alessandro for many years. However, it can now be confirmed that Alessandro, along with his wife and 3 children, returned to live in Rome on 3rd August 1905, consequently, any information relating to the foundry known as Alessandro Parlanti of Parsons Green after this date relates to Ercole Parlanti as sole proprietor. This needs to be kept in mind when reading the section on Alessandro.

It has been suggested that it was Alessandro Parlanti who was responsible for the re-introduction into England of the lost wax process which had been lost for some time (The Illustrated London News of 3rd October 1903). This way of casting is very much still in existence today, and many of the foundries that currently cast by the lost wax process can trace their origins back to either Parlanti, or one of the many art bronze founders who worked at Parlanti’s before setting up on their own: Fiorini, Galizia, Gaskin and Mancini being but some examples. Another source (Duncan James writing on Alfred Gilbert and his use of Nineteenth Century Founding Techniques in ‘Alfred Gilbert Sculptor and Goldsmith’) stated ‘but the arrival of lost wax on a commercial scale may have come with the statue foundry at Parson’s Green, London, which was set up by Parlanti between 1885 and 1893. Having trained at the Fonderia Nelli in Rome, Parlanti brought with him the grog and plaster skills that are still in use today in sculpture foundries of Italian descent. It is also probable that he brought with him the use of gelatine moulds…’.

Before arriving in the UK, Alessandro and Ercole Parlanti both worked at the Fonderia Nelli in Rome, as did their father Antonio. Antonio was born in Bolsena, some 80 miles north of Rome. Antonio moved to Rome, where he worked his way up from labourer to artist in bronze.

Alexandre Nelli, owner of the Fonderia Nelli has, until now, proved somewhat of an enigma due to the lack of information concerning him. A separate page on this website has therefore been devoted to Nelli, as he was of such importance that to not include him would be discourteous.

Richard Dorment mentions the Fonderia Nelli in his book ‘Alfred Gilbert’ whilst at the same time mentioning Parlanti’s arrival in England: ‘Whereas in England by the nineteenth century the secret had been lost, in Rome there existed at least one foundry, the Fonderia Nelli, specialising in the lost wax process. It is not known whether Alfred had dealings with Nelli, but it is significant that the Italian founder who would execute Gilbert’s most exquisite lost wax bronzes in the 1890s, Alessandro Parlanti, had worked at the Fonderia Nelli in the 1880s, and only come (sic) to England in Gilbert’s wake, as it were, to set up his own foundry at 59 Parson’s Green in 1885′.

It is believed that the skill of the art bronze founder will be increasingly appreciated as more information becomes available. The inability of many of the top sculptors (Sir Alfred Gilbert and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska for example) to be able to cast to the highest standard required is proof alone of how a top art bronze founder is far more than simply a factory technician working on the orders of an artist; he is an artisan of note in his own right.

The reputation of the foundries were, of course, only as good as the artisans that were employed there. Perhaps the longest serving Parlanti employee was George Hayter. In 1948, at the age of 74, George reached his 50th year of service with the Parlanti foundries, having started at Parsons Green (Novello Street as he referred to it as) before transferring to West Kensington and then to Herne Bay to work at Conrad Parlanti’s foundry. One of George’s sons, Bill, had his own foundry at Michael Road, Fulham, and William Junior carried on with the Art Bronze Foundry as well.

Some other Parlanti employees have been identified thanks to their families giving information. These artisans have been included in the relevant pages. The 1921 census has yielded further names, and these names are listed in the section on Ercole. Hopefully in time many more of these craftsmen will be discovered, meaning that they can get due recognition

Acknowledgements

The writer of this website is grateful to a great many people and organisations for help and information provided. However, particular thanks go to Louise Boreham, granddaughter of the artist and sculptor Louis Reid Deuchars, for providing extra information, to Chantal Brown for her French translation services and Ellie Pedrazzi for her Italian translation services. Special mention must also go to Stefania Santoni and Raffaella Bruti for their help in providing documentation from Bolsena Library Archives, Claudio Mancini for important documentation retrieved from Rome, and Nicholas Stanley-Price for information about the Nelli foundry.

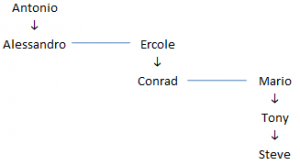

Basic family tree showing descendancy of Steve Parlanti

Steve Parlanti 2019

Parlanti Coat of Arms as produced by Mario Parlanti c.1960