Conrad Parlanti circa 1965

Conrad Parlanti circa 1965

Conrad Parlanti (known as Dino to family) was the eldest child of Ercole Parlanti, and was born in 1903 in Fulham, London. He went to Ackmar Road school in Fulham, as his cousin Riccardo had done some years before him, and he worked in Ercole’s foundry as a youngster.

Photo of a very young Conrad taken from his CR10 Merchant Navy Card

He was a director of E.J.Parlanti & Co. Ltd. before starting a number of different companies, some more successful than others. A work colleague described Conrad as a brilliant caster but a poor businessman. As demand for bronzes reduced, Conrad branched out into other areas. In 1929 Conrad owned a foundry in Teddington, Middlesex which produced not only bronzes, but also worked in copper, lead and glass. Business there was good, leading Conrad to have to advertise for 12 fitters and improvers required for architectural metalwork in an advert placed in The Daily Herald in 1930. Works completed around this period include wrought iron balustrading for High Wycombe’s Majestic Theatre, bronze work at London’s newly built Cambridge Theatre, and the three coloured and lit canopies for another of London’s newly built theatres, The New Victoria (now the Apollo).

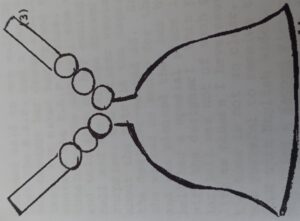

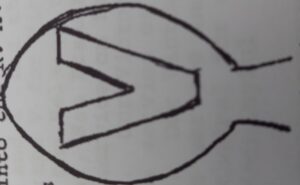

The well known R A F Victory Bell was designed by Conrad. Kay Nelson of the American Bell Association interviewed Conrad by telephone on April 28th 1977, and the following is an account of the Victory Bells given directly by Conrad to Kay word for word.  Sometime during World War II, I was driving to a meeting with Light Alloy Control in Banbury, England. On my way I saw a pile of aluminum ingots in the open field. On inquiring about them, I was told that they were ingots cast from destroyed German aircraft over the United Kingdom. This intrigued me and I thought that on V. E. Day it would be a great relief to everyone to ring in the Peace on Victory Bells cast from metal of destroyed German aircraft. I set about designing a bell. My original design for the bell had a different handle from the ones seen today. The motif I wanted associated with the bell was the ‘’V’’ for Victory so exploited by Winston Churchill and his famous statement, ‘’Never has so much been owed by so many to so few’’. I also wanted to associate the musical signature used by the British Broadcasting System when talking to the people in the occupied countries in Europe. They used the first four notes of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony which by its dot-dot-dot-dash, gave the ‘’V’’ sign in the Morse Code. Originally this correlation between the symphony and Morse Code and the Victory sign had been proposed by a Mr. Victor De Lavalye, then living in exile in London, but who was a member of the Belgian government. Winston Churchill constantly used the ‘’V’’ sign with two upraised fingers. I felt that on V. E. Day, the Bells, by my originally planned handle, could be held by many people, with each person in the line holding on to the other side of the handle. In this way the bells would truly unite the people holding on to the bell handles. I wanted the bells to reach all parts of the United Kingdom and in this way people would become linked together, ringing out their peals of Victory on metal knocked out of the skies during those terribly dark War days.

Sometime during World War II, I was driving to a meeting with Light Alloy Control in Banbury, England. On my way I saw a pile of aluminum ingots in the open field. On inquiring about them, I was told that they were ingots cast from destroyed German aircraft over the United Kingdom. This intrigued me and I thought that on V. E. Day it would be a great relief to everyone to ring in the Peace on Victory Bells cast from metal of destroyed German aircraft. I set about designing a bell. My original design for the bell had a different handle from the ones seen today. The motif I wanted associated with the bell was the ‘’V’’ for Victory so exploited by Winston Churchill and his famous statement, ‘’Never has so much been owed by so many to so few’’. I also wanted to associate the musical signature used by the British Broadcasting System when talking to the people in the occupied countries in Europe. They used the first four notes of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony which by its dot-dot-dot-dash, gave the ‘’V’’ sign in the Morse Code. Originally this correlation between the symphony and Morse Code and the Victory sign had been proposed by a Mr. Victor De Lavalye, then living in exile in London, but who was a member of the Belgian government. Winston Churchill constantly used the ‘’V’’ sign with two upraised fingers. I felt that on V. E. Day, the Bells, by my originally planned handle, could be held by many people, with each person in the line holding on to the other side of the handle. In this way the bells would truly unite the people holding on to the bell handles. I wanted the bells to reach all parts of the United Kingdom and in this way people would become linked together, ringing out their peals of Victory on metal knocked out of the skies during those terribly dark War days.  The ringing of these bells would be reminiscent of the written and musical sign that had maintained the hopes of so many millions of enslaved people, and which would mean that Freedom was being heralded in. I moulded portraits of Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin around the bell and at that time did not intend any wording to be around the bottom of the bell. It was my intention that various factories would make these bells, and they would be sold at an attractive price, and the proceeds would go to the Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund. I never intended to receive any monetary reward from the design or sale of the bells—and I want to stress that I have never received any money in connection with these bells. I made several permanent molds of my design idea and presented them to my associates in the metal field. My dream of the ‘’V’’ handle was knocked out on the grounds that it was too expensive to make the actual open ‘’V’’ handle and the bells would not sell so well because of the higher price tag. I did not object to changing the handle design because of this reasoning (of hopefully getting as much money from the sale of bells into the R.A. F. Benevolent Fund as possible). This is the handle design that was agreed upon and which is the one commonly seen on existing bells:

The ringing of these bells would be reminiscent of the written and musical sign that had maintained the hopes of so many millions of enslaved people, and which would mean that Freedom was being heralded in. I moulded portraits of Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin around the bell and at that time did not intend any wording to be around the bottom of the bell. It was my intention that various factories would make these bells, and they would be sold at an attractive price, and the proceeds would go to the Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund. I never intended to receive any monetary reward from the design or sale of the bells—and I want to stress that I have never received any money in connection with these bells. I made several permanent molds of my design idea and presented them to my associates in the metal field. My dream of the ‘’V’’ handle was knocked out on the grounds that it was too expensive to make the actual open ‘’V’’ handle and the bells would not sell so well because of the higher price tag. I did not object to changing the handle design because of this reasoning (of hopefully getting as much money from the sale of bells into the R.A. F. Benevolent Fund as possible). This is the handle design that was agreed upon and which is the one commonly seen on existing bells:  Solid piece of aluminum ‘’V’’ letter molded onto handle surface, both sides no dot-dot-dot-dash motif. I have been told and shown diagrams by Mrs. Kay Nelson of other handle designs using the dot-dot-dot-dash insignia in several different ways, but this was not used on the original Victory bells. Since I did not even try to obtain a patent on my design, I would assume that factories later took liberties with the original pattern and made various handles and shapes, still using the faces of the three famous men and the several word patterns seen on different bells. I am aware that the bells do not all have the same wording and this I can only attribute to the various factories changing later somewhat the wording just as they did the handles. Additional molds were made at these factories, but most of the factories did not put their factory mark or name inside. There have been bells seen though with a factory name in them. These bells sold for One Pound each and were very popular. Later, I made a mold for some larger bells, but of the same design, and I invited as many as possible of the Battle of Britain boys to come to the foundry and each cast a bell, on which we then inscribed their signatures. These were later brought to the Hungaria Restaurant in London where immediately after the close of the war, soldiers of the Battle of Britain were special guests, and where Flanagan and Allen auctioned off the large bells to famous people attending the gala dinner. All bells were sold at very high prices, the money going to the R. A. F. Benevolent Fund. One bell sold for as high as 1200 Pounds. I believe these bells to be the first bells cast in aluminum alloy on a mass production. Many laughed and told me they would not ring, and that the peal would be flat. This was not so, if the various factories made the rim the thickness I designed. Some factories did not do this, so the tone was not good. The thick rim was necessary for proper tone. I also believe that a large bell cast in aluminum alloy would have all the qualities of a bronze bell at about one-third their weight. However, they must be cast in a permanent mold with a controlled directional solidification. The great irony of this whole story is that all those years when the bells were being made, I would off and on acquire a supply of them and give them away to friends and relatives. I came to the sudden realization that this was a foolish act because the bells then were all sold from the common market, and I did not have a single bell for myself. I finally wrote to the R. A. F. Benevolent Fund asking if they could locate a bell for me. They placed a notice in their magazine, and a lady reading it sent me one of my own designed bells. Her story is indeed curious but I have no reason to dispute her words: it seems to me that this lady living in the south part of England had lost her husband, Freddie, in the War. Her large house and many possessions became far too much for her to manage herself, so she decided to move into an apartment. She gathered up items for sale around the house—a Victory Bell being included. That night she dreamed her deceased husband said to not sell the bell, that the R. A. F. Had a need for it. She thought her dream a silly fantasy, but asked her friend how to contact the R. A. F. Office. Upon obtaining the address, she wrote and told them of her owning such a bell and her strange dream; to her surprise, the officer wrote back about the note in the magazine and the designer: This particular bell was not of such good quality as others I have seen, and the tone is not so clear, but I was grateful to receive the gift from this English widow. Research carried out by Alan Burgdorf, Ed Hendzlik and Rob Roy was published in The Bell Tower magazine of March-April 2011. This shows, with illustrations, the various Victory Bells that had come to light. There were differences in the handles, bell bases, manufacturer and inscriptions. As late as 1979 Conrad’s Victory Bells were still being used in an advert for the R A F Benevolent Fund. This was published in various editions of The Illustrated London News, this advert being in the 27th October edition.

Solid piece of aluminum ‘’V’’ letter molded onto handle surface, both sides no dot-dot-dot-dash motif. I have been told and shown diagrams by Mrs. Kay Nelson of other handle designs using the dot-dot-dot-dash insignia in several different ways, but this was not used on the original Victory bells. Since I did not even try to obtain a patent on my design, I would assume that factories later took liberties with the original pattern and made various handles and shapes, still using the faces of the three famous men and the several word patterns seen on different bells. I am aware that the bells do not all have the same wording and this I can only attribute to the various factories changing later somewhat the wording just as they did the handles. Additional molds were made at these factories, but most of the factories did not put their factory mark or name inside. There have been bells seen though with a factory name in them. These bells sold for One Pound each and were very popular. Later, I made a mold for some larger bells, but of the same design, and I invited as many as possible of the Battle of Britain boys to come to the foundry and each cast a bell, on which we then inscribed their signatures. These were later brought to the Hungaria Restaurant in London where immediately after the close of the war, soldiers of the Battle of Britain were special guests, and where Flanagan and Allen auctioned off the large bells to famous people attending the gala dinner. All bells were sold at very high prices, the money going to the R. A. F. Benevolent Fund. One bell sold for as high as 1200 Pounds. I believe these bells to be the first bells cast in aluminum alloy on a mass production. Many laughed and told me they would not ring, and that the peal would be flat. This was not so, if the various factories made the rim the thickness I designed. Some factories did not do this, so the tone was not good. The thick rim was necessary for proper tone. I also believe that a large bell cast in aluminum alloy would have all the qualities of a bronze bell at about one-third their weight. However, they must be cast in a permanent mold with a controlled directional solidification. The great irony of this whole story is that all those years when the bells were being made, I would off and on acquire a supply of them and give them away to friends and relatives. I came to the sudden realization that this was a foolish act because the bells then were all sold from the common market, and I did not have a single bell for myself. I finally wrote to the R. A. F. Benevolent Fund asking if they could locate a bell for me. They placed a notice in their magazine, and a lady reading it sent me one of my own designed bells. Her story is indeed curious but I have no reason to dispute her words: it seems to me that this lady living in the south part of England had lost her husband, Freddie, in the War. Her large house and many possessions became far too much for her to manage herself, so she decided to move into an apartment. She gathered up items for sale around the house—a Victory Bell being included. That night she dreamed her deceased husband said to not sell the bell, that the R. A. F. Had a need for it. She thought her dream a silly fantasy, but asked her friend how to contact the R. A. F. Office. Upon obtaining the address, she wrote and told them of her owning such a bell and her strange dream; to her surprise, the officer wrote back about the note in the magazine and the designer: This particular bell was not of such good quality as others I have seen, and the tone is not so clear, but I was grateful to receive the gift from this English widow. Research carried out by Alan Burgdorf, Ed Hendzlik and Rob Roy was published in The Bell Tower magazine of March-April 2011. This shows, with illustrations, the various Victory Bells that had come to light. There were differences in the handles, bell bases, manufacturer and inscriptions. As late as 1979 Conrad’s Victory Bells were still being used in an advert for the R A F Benevolent Fund. This was published in various editions of The Illustrated London News, this advert being in the 27th October edition.

One of Conrad’s business enterprises was a general foundry in Herne Bay, Kent. In 1949 he was given the job of repairing and reconditioning the Sheffield War Memorial. As a 22 year old Conrad had worked with his father on the original casting of the memorial. The Herne Bay Press of 26th August 1949 had reported that the memorial had taken quite a battering during WWII, suffering well over a thousand holes and dents. Four men from the Herne Bay foundry travelled up to Sheffield to dismantle the memorial. This involved climbing inside to unbolt the sections of the ten ton, 90 feet high memorial. It was a considerable undertaking to then transport the sections all the way down to Kent. The decision to use Conrad to carry out the repairs was based on the fact that, although the work could have been carried out much nearer to Sheffield, Conrad had worked on the original casting and had intimate knowledge of the memorial, and this was considered too good an opportunity for the authorities to pass up. The Herne Bay Press went on to report on the foundry, mentioning that it had a staff of forty. The first floor housed the offices and administration department, with laboratories at the top. The foundry had suffered a recent fire, in which part of the roof had been destroyed, this had handicapped production. The foundry had as much work as it could handle, and the future looked bright for what was described as Herne Bay’s only ‘heavy industry’.

An interesting article appeared in the Herne Bay Press of Friday 30th December 1949, and is reproduced here in full as it includes mention of Ercole as still being very much active. I myself had the pleasure of meeting Charles McKinnon (referred to in the article) in November 2015.

Conrad Parlanti Castings’ Staff Lunch

Firm’s Development at Herne Bay

The intense international interest that is being taken in Herne Bay’s only light industry-Conrad Parlanti Castings-may mean that this rapidly developing firm, engaged on important work, will have to move to more extensive premises in an area where its staff can be adequately housed, if the facilities for expansion and accommodation are nor forthcoming.

At a Christmas lunch for members of the firm, held at the Grand Hotel on Thursday last week, and M.P.-Mr. F. Skinnard (East Harrow)-paid tribute to the team spirit with which the firm is infected, praised the workers for what they had done in the past, but warned of the vast amount still to be done.

He praised them for the fact that such was their interest in the work that they were on the job all hours of the day and night, as well as Sundays.

‘’At any rate there is one corner of the British Isles where greater effort does not have to be called for. You really have put your backs into it.’’

Cheerful Company

The company, presided over by Mr. E. J. Parlanti, ‘’father’’ of the firm, sat down to lunch beneath balloon clusters and other colourful manifestations of the season. About forty were present and the high spirited assembly was soon busy pulling crackers and donning paper hats.

Other officials present were Mr. C. A. Parlanti, F. I. M., principal, Mr. C. C. McKinnon, general manager, Mr. V. C. MacDonnell, development manager, Mr. John E. Pyne, production engineer; and Mr. P. Hamilton-Jenkins, works manager of Parlanti Castings (Ireland) Ltd., of which Mr. Conrad Parlanti and Mr. McKinnon are directors. The speakers were introduced to Mr. Pyne.

Extending a welcome to Mr. And Mrs. Skinnard, Mr. J. MacGeorge recalled Mr. Skinnard’s recent visit to the factory, when, he said, they were all impressed by the questions he asked and the way he grasped the various processes he was shown.

‘’Friend of the Family’’

Since he had left they had one of their finest allies, for although he was an M. P., which gave him plenty to do, he was available to them at almost any time; he had delegated none of the work, but had taken it in himself right at the top of the tree. They welcomed him as a friend of the family and all of them.

The paper-hatted company rose to honour the toast and, responding, Mr. Skinnard agreed that he was kept extremely busy with the work associated with his position.

He was interested in the firm’s activities because there were physical repercussions in their work which they themselves perhaps did not realise. The factory was one of the most significant industrial units working in the country to-day.

He mentioned that every member of the firm was present that day, except their oldest, Mr. George Hayter, and expressed his regret that indisposition prevented his attendance.

Development of the Work

Observing that the ‘’father’’ of the ‘’lost wax’’ process was in the chair, Mr. Skinnard declared that if they did no more than carry on the Parlanti tradition in ‘’lost wax’’ casting, they would have done well, but later pointed out that the work was developing to such an extent that in a short while they would regard this process as antediluvian.

He read a telegram containing best wishes for Christmas from their factory in Ireland: they had, he said, a pioneer in ‘’lost wax’’ in Mr. Hamilton-Jenkins, works manager of the Irish offspring.

Mr. Skinnard went on to explain that the factory had settled in Herne Bay so as to remain undisturbed by prying eyes, and said they had tackled and solved some of the problems that had puzzled metallurgists throughout the world.

‘’Wasted Money’’

When he heard of the hundreds of thousands of pounds poured out on abortive experiments, he was both amazed and gratified at the results they had achieved.

He spoke of the technical skill of Mr. Conrad Parlanti and said it was a rare case of genius passing from father to son; he was, he declared, one of the finest metallurgists working to-day.

After paying tribute to other officials, the speaker applied to their work Napoleon’s famous expression, ‘’If it is difficult, it is already done: if impossible it will take some time.’’ He was, he said, proud of the work they had done and of the way they had entered into the spirit of the times. Their process would bring them fame and material benefit in the future.

Mr. F. Taylor thanked Mr. Skinnard for his address and Mr. A. E. Palmer, associated with the firm for many years, proposed a toast to Mr. E. J. Parlanti, an international authority on art reproduction in metal.

‘’World’s Best Crowd’’

A brief address was given by Mr. Hamilton-Jenkins, and Mr. Parlanti, senior, who replied, said: ‘’As far as I am concerned you are the best crown in the world.’’

In the evening there was dancing to the music of Basil Quested, and his trio, and a cabaret, compered by Mr. D. Harley, was given by members of the firm.

The turns were as follows: ‘’The Sooty-Soots’’ (Messrs. Neame, Taylor and Newman); Mr. S. Patrick; comic horse on skates (Messrs. Philwine and Neame); ‘’McAndrew in the Rough’’ (Messrs. Blackburn and Neame); and Mr. F. Taylor (eccentric dancing).

The company enjoyed community singing and various novelty items and elimination waltzes and foxtrots took place.

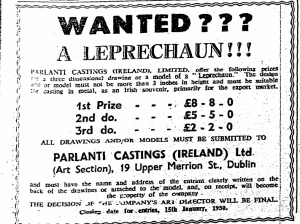

In late 1949 Conrad had decided to set up a bronze foundry in Ireland, the idea being to manufacture bronze leprechauns for export primarily to the USA. Conrad wanted to set the company up to be run solely by the Irish after initially bringing over craftsmen from his foundry in Herne Bay, Kent to train Irish workers. An advertisement was taken out in The Irish Times stating ‘Wanted??? A Leprechaun!!!’ inviting designs and or models for his venture, with a first prize of eight pounds and eight shillings for the winning design.  After receiving about seventy models and one hundred drawings, it was decided that the winner would also almost certainly receive a royalty based on sales. On 27th March the winners were announced in the Irish Independent, those winners being Miss Jean Hoctor, of 78 Harcourt Street, Dublin, who won first prize, Giacomo Brodi of Cove House, Sandycove, Dublin, who won second prize, and Miss Maureen O’Sullivan of Audley Place, St. Patrick’s Hill, Cork, who won third prize.

After receiving about seventy models and one hundred drawings, it was decided that the winner would also almost certainly receive a royalty based on sales. On 27th March the winners were announced in the Irish Independent, those winners being Miss Jean Hoctor, of 78 Harcourt Street, Dublin, who won first prize, Giacomo Brodi of Cove House, Sandycove, Dublin, who won second prize, and Miss Maureen O’Sullivan of Audley Place, St. Patrick’s Hill, Cork, who won third prize.

From the Irish Independent 6th July 1950

From the Irish Independent 6th July 1950

A dispute at the Finglas Foundry occurred on Monday 21st August 1950. Pickets were placed outside the premises, as ten members of staff who were members of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union went on strike. They were claiming a minimum rate of 2/6 per hour. The dispute was short lived, by the Thursday of the same week a settlement had been agreed and the ten strikers had returned to work.

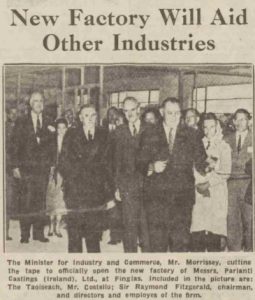

In November 1951, it was announced that the ‘factory’ would soon be supplying component parts for the assembly of tractors in England. This was to be on a large scale following the firm entering into an agreement with Ferguson tractor manufacturers of Coventry. The contract had been won despite facing strong competition, and a large part of the decision taken to use Parlanti’s was based on the promise of the supply of the highest quality castings. It was also mentioned at the time that Parlanti’s had also secured a contract with the Dunlop Rubber Company for the production of precision castings of aluminium alloys for use in Dunlop factories in England.

Unfortunately, due to bad management, the company went into voluntary liquidation, defaulting on a loan given by the Irish government.

In 1952, the Carron Company of Falkirk, Scotland showed an interest in the Herne Bay foundry along with a number of patents that Conrad had registered. Carron purchased a controlling interest and Carron Parlanti Limited was formed, making Niforge castings in aluminium, iron and steel by the Parlanti Mould Process for aircraft and radar systems. The Parlanti Casting Process was designed by Conrad. Conrad emigrated to the USA in 1955, settling at first on the East coast and working with General Communications in Boston, later with Gorham Silver of Providence. He was awarded the degrees of D.Sc. and Ph.D. from Bari University in Italy in 1957. 1962 saw Conrad become a naturalised USA citizen whilst living in Massachusetts. Conrad finally settled on the West coast. In keeping with his character, Conrad continued to develop further business interests, which included infrared photography, and was even patenting designs as late as 1981. Whilst president of Conrad A Parlanti & Associates of Berkeley California, he was appointed casting consultant to NASA’s Ames research centre. Conrad worked right up to his death in 1984. Having worked since a young man in foundries, a difficult, dirty and physical job, he was able to pass on good advice. ‘Never’ he said ‘lift anything heavier than a pen to earn a living’. Conrad’s daughter, Theodora Parlanti, was a talented artist. In 1959 she was elected a Fellow of The Royal Society of Arts in London for her work in the fields of oil painting and interior design.